Photos composers

Photos performers

EARPLAY 25: Outside In

Monday, March 22, 2009

7:30 p.m.

6:45 p.m. (pre-concert talk)

Herbst Theatre

The Earplay Ensemble

Mary Chun, conductor

Tod Brody, flutes • Peter Josheff,

clarinets

Terrie Baune, violin • Ellen Ruth

Rose, viola • Thalia Moore, cello,

Karen Rosenak, piano

Guest Artists

Carolina Eyck, theremin

Jan Bilk

Stigma integrum (2005)

theremin, string quintet

Virtuoso thereminist, Carolina Eyck gives a special performance of a movement from Stigma integrum concerto. One of a few musicians worldwide to master the only instrument ever created that does not require physical contact, this is a rare opportunity for San Francisco audiences to hear a live performance. A pioneering electronic instrument invented in 1919 by Leon Theremin, a Russian physicist and cellist, the theremin contains an antennae and a rod to control pitch and volume by manipulating the magnetic field. Virtuoso thereminist, Carolina Eyck gives a special performance of a movement from Stigma integrum concerto. One of a few musicians worldwide to master the only instrument ever created that does not require physical contact, this is a rare opportunity for San Francisco audiences to hear a live performance. A pioneering electronic instrument invented in 1919 by Leon Theremin, a Russian physicist and cellist, the theremin contains an antennae and a rod to control pitch and volume by manipulating the magnetic field.

Ms. Eyck's appearance is sponsored by the San Francisco Ballet and is in conjunction with the U.S. premiere of The Little Mermaid.

Jan Bilk (b. 1958, Germany) received his diploma at the Hochschule für Musik "Hanns Eisler" in Berlin for piano, accordion and composition. Later he was appointed with a lectureship at the same university for synthesizer and computer music. He has produced and composed numerous radio plays, written film music and staged spectacular multimedia concerts and shows. Today he works as a composer and producer including writing chamber and orchestra music for the theremin. Jan Bilk is also head of the publishing house "Servi" in Berlin.

In his work "Stigma integrum" for theremin and string quintet, written in 2005, Bilk works with musical motives from a small group of Sorbic-Slavic people who live in Bilk's homeland in the eastern part of Germany.

Jonathan Harvey

The Riot (1993)

flute/piccolo, bass clarinet, piano

The Riot seems to take "the dance" as its basic raison d'etre. From the title you might expect some chaotic din to be the principle mode of expression, but in fact, it's a much more controlled gathering of thematic characters. The main formal gist of the piece seems to be a series of clear sections (though with very smooth elisions between them), each based more upon a textural idea than a thematic one: irregular dance-like figures, upwards sequences (reminiscent, perhaps, of Shepard's tones), etc. The Riot, perhaps owing to its orchestration and its dancelike nature, owes a small debt to Stravinsky: the opening of the piece sounds somewhat like Symphonies for Wind Instruments.

—Christopher Bailey (New York, New York, USA)

The Riot was commissioned by the University of Bristol with funds provided in part by South West Arts. It was first performed by the Het Trio at St. Georges, Brandon Hill, Bristol on March 28, 1994.

JONATHAN HARVEY (b.1939, England) was a major music scholar at St John's College, Cambridge. He gained doctorates from the universities of Glasgow and Cambridge and also studied privately (on the advice of Benjamin Britten) with Erwin Stein and Hans Keller. He was a Harkness Fellow at Princeton (1969-70). In the 1980’s he was invited to work at IRCAM in Paris and led to his interest in electronic music where he composed eight major works. Harvey has also composed for most other genres: orchestra, chamber, as well as works for solo instruments. He has produced a large output of choral works, including the large cantata with electronics Mothers shall not Cry (2000). His music has been extensively played and toured by Ensemble Modern, Ensemble Intercontemporain, and Ictus Ensemble of Brussels. About 50 recordings are available on CD. He regularly performed at all the major international contemporary music festivals, and is one of the most skilled and imaginative composers working in electronic music. JONATHAN HARVEY (b.1939, England) was a major music scholar at St John's College, Cambridge. He gained doctorates from the universities of Glasgow and Cambridge and also studied privately (on the advice of Benjamin Britten) with Erwin Stein and Hans Keller. He was a Harkness Fellow at Princeton (1969-70). In the 1980’s he was invited to work at IRCAM in Paris and led to his interest in electronic music where he composed eight major works. Harvey has also composed for most other genres: orchestra, chamber, as well as works for solo instruments. He has produced a large output of choral works, including the large cantata with electronics Mothers shall not Cry (2000). His music has been extensively played and toured by Ensemble Modern, Ensemble Intercontemporain, and Ictus Ensemble of Brussels. About 50 recordings are available on CD. He regularly performed at all the major international contemporary music festivals, and is one of the most skilled and imaginative composers working in electronic music.

Judith Weir

The Art of Touching the Keyboard (1983)

piano

This work was commissioned by William Howard with funds provided by the Arts Council of Great Britain, and was first performed in the Wigmore Hall, London on 31 May 1983.

The title of this music is an over-literal translation of the title of Francois Couperin's harpsichord tutor of 1716, L'art de toucher le clavecin. -- J.W.

Michael Finnissy and Judith Weir have carried on a musical dialog since the late 1970’s, sharing a deep appreciation of ancient through modern history, and both western and world musics, as well as a great sense of fun in their musical responses to their influences and to each other. There is no particular relationship between the two pieces on tonight’s concert, but there are, nevertheless, some resonances.

Weir numbers The Art of Touching the Keyboard among several pieces she composed for her friends that she continues to enjoy hearing:

The Art of Touching the Keyboard was written for William Howard (pianist). I borrowed the title from Francois Couperin (‘L’Art de toucher le clavecin’) but not much else. This single movement (fast-slow-fast) piano sonata

explores the range of piano ‘touch’ from the gentle stroke to the violent assault.

Indeed, the piece explores not only the gamut of ‘touches’ but also compositional techniques: rhythmic augmentation and diminution, contrapuntal inversion, scales and their harmonizations; keyboard effects; and a seemingly arbitrarily applied kaleidoscope of dynamics, At times the piece sounds like a fractured version of Czerny’s School of Velocity. And always, there is much wit in evidence, Dominant seventh chords suddenly appear, bringing floating phrases to abrupt and crude-sounding cadence, but technically correct, as the required penultimate chord in a musical phrase (except that Weir’s dominant sevenths rarely resolve). Weir seems to be making light of musical tutors of every kind, demonstrating emphatically that mere knowledge of music fundamentals and skills is no guarantee of musical understanding or expression.

As Weir noted, the piece is cast in three continuous movements, but the division is somewhat masked by the surface texture which is constantly changing. There is, however, a chorale-like passage which concludes both the first and third “fast” sections. The “slow” second movement broadens and expands the chorale material to include a funny little central scherzo-like section, then returns to the chorale, culminating in a cadenza punctuated by glissandi. The piece begins and ends on repeated B naturals, separated by irregularly measured silences. -- Karen Rosenak,

Judith Weir was born near Cambridge in 1954. She studied composition briefly with John Taverner and Robin Holloway at Cambridge University. Inspired by medieval history and in particular the mythology of Scotland, she is probably best known for her operas and theater works. The very setting of her opera King Harald’s Saga (1979) was and is striking -- a ten-minute piece for solo soprano, singing (a cappella) eight different roles. She has also written a considerable amount of chamber and orchestral music. Her music evidences pronounced textural clarity and an equally distinctive harmonic palette. Judith Weir was born near Cambridge in 1954. She studied composition briefly with John Taverner and Robin Holloway at Cambridge University. Inspired by medieval history and in particular the mythology of Scotland, she is probably best known for her operas and theater works. The very setting of her opera King Harald’s Saga (1979) was and is striking -- a ten-minute piece for solo soprano, singing (a cappella) eight different roles. She has also written a considerable amount of chamber and orchestral music. Her music evidences pronounced textural clarity and an equally distinctive harmonic palette.

Freightrain Bruise makes clear reference to jazz keyboard style (extrovert Blues), a type of improvisation I used to accompany Matt Mattox’s jazz-dance classes, and which I found and appropriated from the recordings of Errol Garner, Thelonius Monk, Art Tatum (one of Leopold Godowsky’s favorite pianists!) and plenty of others. The harmonic distortions and awkward gaps in the textural flow do not stem from this tradition though, and constitute-fancifully perhaps- ‘bruises’ on its surface, places where the ripe fruit of jazz hit the cold floor of late twentieth century ‘angst’!

The “harmonic distortions and awkward gaps” Finnissy refers to in his piece occur in Judith Weir’s piece as well. The silences provided by long rests in both pieces are startling and uncomfortable.

Both pieces exhibit reverence for, joyful embrace of, and finally, a poke in the ribs, at well-established precedents. It seemed fitting to pair these pieces together.

Judith Weir (b. 1954 Scotland) grew up near London. She was an oboe player, performing with the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain, and had a few composition lessons with John Tavener during her schooldays. She attended Cambridge University, where her composition teacher was Robin Holloway, and on leaving there spent several years as a community musician in rural southern England. She then returned to Scotland to work as a university teacher in Glasgow. Since the 1990s she has been based in London, and was artistic director of the Spitalfields Festival for six years. She has continued to teach, most recently at Cardiff University, from 2006-9. In December 2007, she was presented with the Queen’s Medal for Music by HM The Queen and Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Master of the Queen’s Music. In January 2008, over fifty over her works for all possible media were performed during Telling The Tale, a three-day retrospective of her music, hosted by the BBC Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican Centre, London.

Judith Weir is now at work on a new opera which will receive its first performances at the Bregenzer Festspiele, Austria, in 2011. Her music is published exclusively by Chester Music Ltd. and Novello and Co. Ltd.

Courtesy of Chester Music Ltd. and Novello and Co. Ltd.

Michael Finnissy

Freight Train Bruise (1972-1980)

piano

He revised many of his dance improvisations to become concert piano pieces. Freightrain Bruise appears in a collection of his piano pieces whose titles attest to his involvement with dance (Mazurka, Two Pasodobles, Kemp;s Morris, and three Strauss-Waltzer,), and it was one of many pieces written for his dance colleagues—in this case, Charlotte Holtzermann. As might be expected, his music has a highly improvisatory, unpredictable and utterly mind-boggling character. It is technically demanding, yet clearly indicative of his own extraordinary keyboard facility.

Freightrain Bruise makes clear reference to jazz keyboard style (extrovert Blues), a type of improvisation I used to accompany Matt Mattox’s jazz-dance classes, and which I found and appropriated from the recordings of Errol Garner, Thelonius Monk, Art Tatum (one of Leopold Godowsky’s favorite pianists!) and plenty of others. The harmonic distortions and awkward gaps in the textural flow do not stem from this tradition though, and constitute-fancifully perhaps- ‘bruises’ on its surface, places where the ripe fruit of jazz hit the cold floor of late twentieth century ‘angst’!

The “harmonic distortions and awkward gaps” Finnissy refers to in his piece occur in Judith Weir’s piece as well. The silences provided by long rests in both pieces are startling and uncomfortable.

Both pieces exhibit reverence for, joyful embrace of, and finally, a poke in the ribs, at well-established precedents. It seemed fitting to pair these pieces together. -- Karen Rosenak

Michael Finnissy (b. 1946, London) He reports that he began composing as soon as he began piano lessons at the age of four. He supported his advanced music studies by accompanying for dance classes, both classic ballet and jazz, and studied with Bernard Stevens and Humphrey Searle at the Royal College of Music, later Roman Vlad in Italy. He taught in the music department at the London School of Contemporary Dance from 1969-1974. .He is a formidable pianist as well as a prolific composer, and also much in demand as a conductor. Michael Finnissy (b. 1946, London) He reports that he began composing as soon as he began piano lessons at the age of four. He supported his advanced music studies by accompanying for dance classes, both classic ballet and jazz, and studied with Bernard Stevens and Humphrey Searle at the Royal College of Music, later Roman Vlad in Italy. He taught in the music department at the London School of Contemporary Dance from 1969-1974. .He is a formidable pianist as well as a prolific composer, and also much in demand as a conductor.

He revised many of his dance improvisations to become concert piano pieces. Freightrain Bruise appears in a collection of his piano pieces whose titles attest to his involvement with dance (Mazurka, Two Pasodobles, Kemp;s Morris, and three Strauss-Waltzer,), and it was one of many pieces written for his dance colleagues—in this case, Charlotte Holtzermann. As might be expected, his music has a highly improvisatory, unpredictable and utterly mind-boggling character. It is technically demanding, yet clearly indicative of his own extraordinary keyboard facility. --K.R.

Lori Dobbins

Through the Golden Gate (2009)

World premiere

Earplay commission

flute, clarinet, violin, viola, piano

It was a great pleasure to compose a piece for Earplay’s 25th anniversary season. Over the past 25 years, Earplay has established itself as one of San Francisco’s premiere new music ensembles and is renowned throughout the country. I have had the opportunity to work with Earplay several times and jumped at the chance to continue our collaborations.

On the occasion of Earplay’s 25th anniversary season it seemed appropriate to write a piece about the beautiful city of San Francisco. Having grown up primarily in the Bay Area and having lived here for more than thirty years, I left my heart in San Francisco and miss it a great deal – the cool, enveloping fog, the dramatic coastline, seagulls riding the wind as it whips up waves in the bay, the constantly changing view of the Golden Gate Bridge as the fog blows over and through the towers and suspension cables – this sight always inspires me! So even though I do not believe music can literally represent a place the way a painting or photograph can, this piece is a musical imagining of day moving into night in the vicinity of the Golden Gate Bridge.

The piece is primarily concerned with color and harmony, though melodic passages also occur, particularly in the flute, which employs a number of extended techniques. The ensemble is often used to create a kaleidoscope, with colors and patterns constantly changing and moving in and out of focus. The overall form is directional – from the use of sound for its own sake with the clusters, glissandi, harmonics, pizzicato, etc., to the prominent flute melody and later contrapuntal flute and clarinet melodies, to the use of the entire ensemble creating rich harmonies and colors over a wide register, and finally to the coda, which reflects material used earlier in the piece as a reminiscence.

I realize that without this description, the listener would most likely imagine something other than what I sought to portray. However, I believe the dramatic arc of the piece can be perceived as a progression from early morning to late at night, with the light of glittering stars dancing on the waves.

.

Many thanks to the wonderful musicians of Earplay for premiering this piece! -- L.D.

Lori Dobbins studied composition at San Jose State University, California Institute of the Arts and the University of California, Berkeley. Her principal teacher was Mel Powell. She currently teaches at the University of New Hampshire. Dobbins has received commissions from the Koussevitzky Foundation, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, Fromm Foundation, and Earplay. Fellowships and awards she has received include the Goddard Lieberson Fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Lili Boulanger Award from the National Women Composers Resource Center, and residencies at the MacDowell Colony. Her works have been performed by the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, Cleveland Chamber Symphony, Collage, New Music Consort, New Jersey Percussion Ensemble, San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, Earplay, and numerous other ensembles. Several of her works are published by G. Schirmer and recordings are available on the Vienna Modern Masters series and Capstone Records. Lori Dobbins studied composition at San Jose State University, California Institute of the Arts and the University of California, Berkeley. Her principal teacher was Mel Powell. She currently teaches at the University of New Hampshire. Dobbins has received commissions from the Koussevitzky Foundation, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, Fromm Foundation, and Earplay. Fellowships and awards she has received include the Goddard Lieberson Fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Lili Boulanger Award from the National Women Composers Resource Center, and residencies at the MacDowell Colony. Her works have been performed by the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, Cleveland Chamber Symphony, Collage, New Music Consort, New Jersey Percussion Ensemble, San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, Earplay, and numerous other ensembles. Several of her works are published by G. Schirmer and recordings are available on the Vienna Modern Masters series and Capstone Records.

Intermission

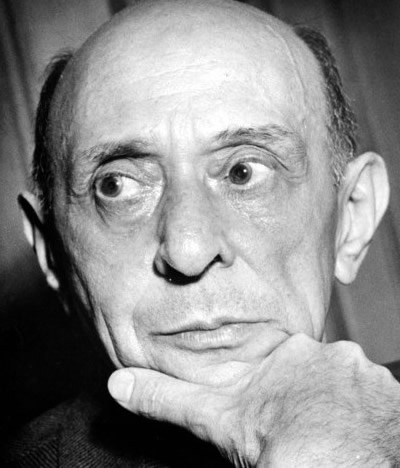

Arnold Schoenberg

Trio, op.45 (1946)

violin, viola, cello

The String Trio op. 45 was commissioned by the music department of Harvard University for a symposium on Musical Criticism in spring 1947. It was premiered by members of the Walden String Quartet at Harvard May 1, 1947. Other composers contributing works for the occasion include Hindemith, Malipiero, Copland and Martinu. Schönberg had begun work on the piece already in June 1946, but the majority was composed between August 20 and September 23-only two and a half weeks after Schönberg suffered a severe heart attack. This traumatic episode, which Schönberg survived only through an injection directly into his heart, took its toll on the 71 year old composer and it is said that this Trio reflected his physical and psychological suffering during this period.

The single movement work is divided into five sections: three “parts” and two “episodes.” Part three begins like Part one and recaps aspects of the whole work. Thematic development is spread throughout the work. The piece ends with a 12-note statement in the violin in which the basic motifs are presented. The variety of surface details (abrupt dynamic contrasts, expressionistic string effects, variations in tone color) stand in contrast to the rigorous serialism that underpins the work’s structure.

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), born in Austria and immigrated to the U.S. in 1933, was a composer whose discovery of the "method of composition with twelve tones" radically transformed 20th-century music. Most important musical developments of the second half of the 20th century owe their impetus directly or indirectly to him. While mainly self-taught he had teaching posts at several prestigious institutions including the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, the University of Southern California and U.C., Los Angeles. Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), born in Austria and immigrated to the U.S. in 1933, was a composer whose discovery of the "method of composition with twelve tones" radically transformed 20th-century music. Most important musical developments of the second half of the 20th century owe their impetus directly or indirectly to him. While mainly self-taught he had teaching posts at several prestigious institutions including the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, the University of Southern California and U.C., Los Angeles.

top |

Virtuoso thereminist, Carolina Eyck gives a special performance of a movement from Stigma integrum concerto. One of a few musicians worldwide to master the only instrument ever created that does not require physical contact, this is a rare opportunity for San Francisco audiences to hear a live performance. A pioneering electronic instrument invented in 1919 by Leon Theremin, a Russian physicist and cellist, the theremin contains an antennae and a rod to control pitch and volume by manipulating the magnetic field.

Virtuoso thereminist, Carolina Eyck gives a special performance of a movement from Stigma integrum concerto. One of a few musicians worldwide to master the only instrument ever created that does not require physical contact, this is a rare opportunity for San Francisco audiences to hear a live performance. A pioneering electronic instrument invented in 1919 by Leon Theremin, a Russian physicist and cellist, the theremin contains an antennae and a rod to control pitch and volume by manipulating the magnetic field. JONATHAN HARVEY

JONATHAN HARVEY Judith Weir was born near Cambridge in 1954. She studied composition briefly with John Taverner and Robin Holloway at Cambridge University. Inspired by medieval history and in particular the mythology of Scotland, she is probably best known for her operas and theater works. The very setting of her opera King Harald’s Saga (1979) was and is striking -- a ten-minute piece for solo soprano, singing (a cappella) eight different roles. She has also written a considerable amount of chamber and orchestral music. Her music evidences pronounced textural clarity and an equally distinctive harmonic palette.

Judith Weir was born near Cambridge in 1954. She studied composition briefly with John Taverner and Robin Holloway at Cambridge University. Inspired by medieval history and in particular the mythology of Scotland, she is probably best known for her operas and theater works. The very setting of her opera King Harald’s Saga (1979) was and is striking -- a ten-minute piece for solo soprano, singing (a cappella) eight different roles. She has also written a considerable amount of chamber and orchestral music. Her music evidences pronounced textural clarity and an equally distinctive harmonic palette. Michael Finnissy (b. 1946, London) He reports that he began composing as soon as he began piano lessons at the age of four. He supported his advanced music studies by accompanying for dance classes, both classic ballet and jazz, and studied with Bernard Stevens and Humphrey Searle at the Royal College of Music, later Roman Vlad in Italy. He taught in the music department at the London School of Contemporary Dance from 1969-1974. .He is a formidable pianist as well as a prolific composer, and also much in demand as a conductor.

Michael Finnissy (b. 1946, London) He reports that he began composing as soon as he began piano lessons at the age of four. He supported his advanced music studies by accompanying for dance classes, both classic ballet and jazz, and studied with Bernard Stevens and Humphrey Searle at the Royal College of Music, later Roman Vlad in Italy. He taught in the music department at the London School of Contemporary Dance from 1969-1974. .He is a formidable pianist as well as a prolific composer, and also much in demand as a conductor.  Lori Dobbins studied composition at San Jose State University, California Institute of the Arts and the University of California, Berkeley. Her principal teacher was Mel Powell. She currently teaches at the University of New Hampshire. Dobbins has received commissions from the Koussevitzky Foundation, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, Fromm Foundation, and Earplay. Fellowships and awards she has received include the Goddard Lieberson Fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Lili Boulanger Award from the National Women Composers Resource Center, and residencies at the MacDowell Colony. Her works have been performed by the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, Cleveland Chamber Symphony, Collage, New Music Consort, New Jersey Percussion Ensemble, San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, Earplay, and numerous other ensembles. Several of her works are published by G. Schirmer and recordings are available on the Vienna Modern Masters series and Capstone Records.

Lori Dobbins studied composition at San Jose State University, California Institute of the Arts and the University of California, Berkeley. Her principal teacher was Mel Powell. She currently teaches at the University of New Hampshire. Dobbins has received commissions from the Koussevitzky Foundation, Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, Fromm Foundation, and Earplay. Fellowships and awards she has received include the Goddard Lieberson Fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, Lili Boulanger Award from the National Women Composers Resource Center, and residencies at the MacDowell Colony. Her works have been performed by the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, Cleveland Chamber Symphony, Collage, New Music Consort, New Jersey Percussion Ensemble, San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, Earplay, and numerous other ensembles. Several of her works are published by G. Schirmer and recordings are available on the Vienna Modern Masters series and Capstone Records. Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), born in Austria and immigrated to the U.S. in 1933, was a composer whose discovery of the "method of composition with twelve tones" radically transformed 20th-century music. Most important musical developments of the second half of the 20th century owe their impetus directly or indirectly to him. While mainly self-taught he had teaching posts at several prestigious institutions including the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, the University of Southern California and U.C., Los Angeles.

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), born in Austria and immigrated to the U.S. in 1933, was a composer whose discovery of the "method of composition with twelve tones" radically transformed 20th-century music. Most important musical developments of the second half of the 20th century owe their impetus directly or indirectly to him. While mainly self-taught he had teaching posts at several prestigious institutions including the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin, the University of Southern California and U.C., Los Angeles.