Origins of Notation

Contents

Saint Isidore's Declaration

Once upon a time, there was writing, but not music notation. Authors could record their words in books for posterity; although musicians sang and played instruments, their melodies vanished in the moment. In the middle of the 7th century, Isidore of Seville wrote a twenty-book encyclopedia in which he summarized the knowledge of the world. In it, he stated that melodies could not be written down, and, as one would expect from this declaration of impossibility, it included no music notation. [1]

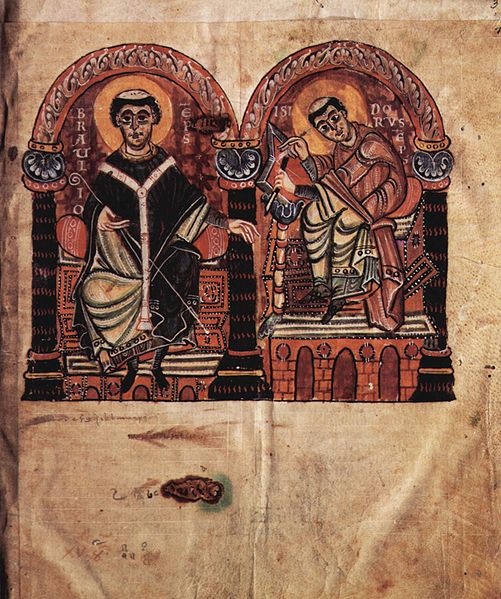

Saint Isidore as portrayed in a tenth-century manuscript (on the right). [2]

| [1] | Grove Music Online, "Notation" §III, 1 |

| [2] | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isidore_of_Seville |

The Seikilos Tablet

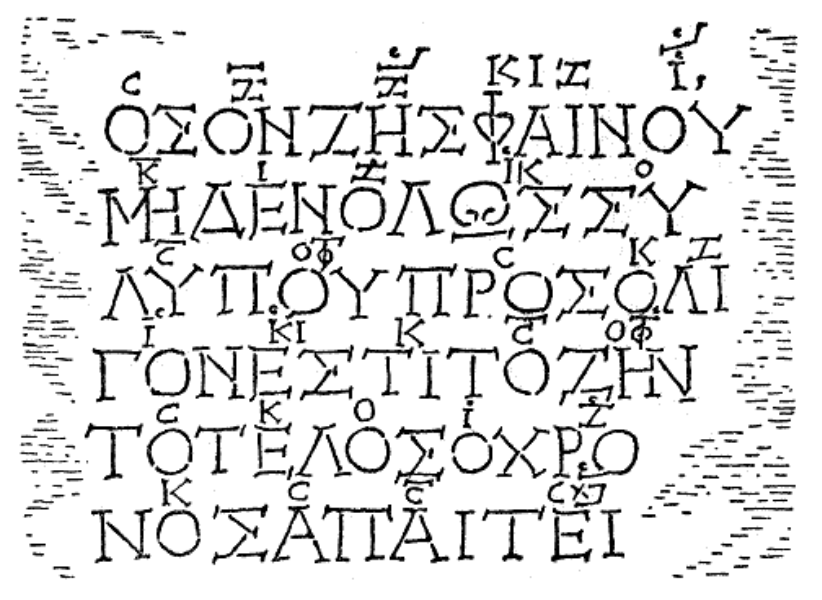

Strictly speaking, Saint Isidore was wrong. Melodies could be written down, because they had been written down by the ancient Greeks. In 1883, around the same time Edison was complicating the history of sound-writing with the invention of the phonograph, the Scottish archeologist Sir William Mitchell Ramsay complicated it with his own discovery of the "oldest complete musical composition ever found." [3] In Asia Minor (modern Turkey), in the first century AD, the Greek poet Seikilos had composed a song in memory of his wife Euterpe, which he chiseled in everlasting stone:

the Seikilos epitaph in ancient notation [4]

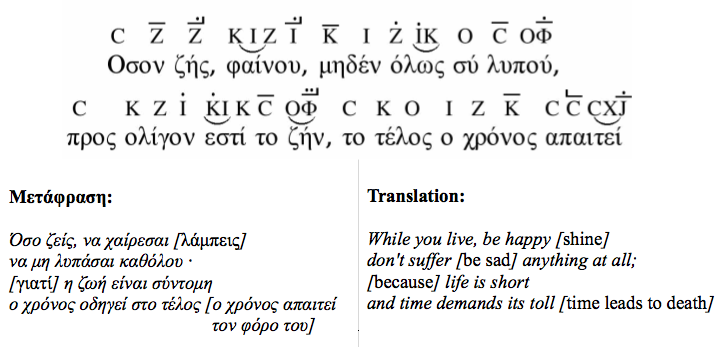

the epitaph rewritten in polytonic script, with the poem in translation

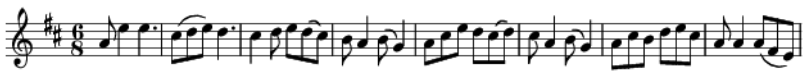

the melody of the epitaph in modern Western notation

| [3] | "Seikilos Epitaph", from http://imslp.org/wiki/Seikilos_Epitaph_(Ancient_Greek) |

| [4] | Ibid. |

Such durable examples of music from the ancient world are rare. I am no expert on ancient Greek music notation, so I will note merely that the epitaph, unlike most fragments of ancient Greek music, is "apparently complete and without extraordinary textual (i.e., notational) problems," according to someone who should know what he's talking about. [5] Two millennia after Seikilos carved his musical monument, we too may celebrate Euterpe's memory, which is also the memory of music literacy itself. Together, let us sing her song of praise, which is also praise for notation's power to "pass on to the senses of others what would otherwise fade away in the present." [6]

| [5] | Jon Solomon, "The Seikilos Inscription: A Theoretical Analysis", American Journal of Philology, Vol. 107 No. 4, 457 |

| [6] | Kittler, "Number and Numeral", 57 |

How did the ancient notation work? How does it relate to the notation we've learned through music lessons and musicianship classes? Again, without overstepping my bounds, I can point out the basic facts. The lines of the poem run underneath letters representing the melody's pitches. Works by ancient Greek music theorists such as Aristoxenus explain the relationship between the arbitrary alphabetic scheme and the interval ratios of the monochord; by following their explanations, we can translate the letters first into numbers, and then into more familiar music notation. Lines and dashes over the letters represent different rhythmic values; a dashed letter, for example, generally represents a value twice as long as an unmarked letter. Again, ancient Greek music theory explains the proportions, and enables a translation. The alphabetic notation of the epitaph thus accounts for the two musical parameters most familiar to us: pitch and rhythm.

The Reinvention of Writing

By the Dark Age of Saint Isidore, Europeans had lost the musical knowledge of the ancient Greeks. In the ninth century, the Franks rediscovered or reinvented music writing in order to promulgate their chants throughout Charlemagne's kingdom. Their notation system, however, bore no discernible relation to that of the ancients, or to our own. Rather, it consisted of staffless neumes–that is, cursive blips and squiggles of ink lacking common measure:

Staffless neumes. [7]

| [7] | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregorian_chant#Notation_2 |

We can imagine this notation as an ancient sort of acousmatic writing: a compromise between, on one hand, discrete symbols representing distinct pitches, and, on the other, continuous contours representing, perhaps, vocal slides and inflections. A table from Grove Music Online indicates the complexity of this system, its lack of standardization, and the challenges of translating it into modern notation:

Neumes of the 10th–11th centuries. [8]

| [8] | Grove Music Online, "Notation" §III, 1 |

Although we can sing the praises of Euterpe with confidence, the divine music of the Franks is, for all practical purposes, lost, because we have forgotten how to read it. The point to glean from this example, however, is not that pitch and rhythm "always win"—that they are the only parameters capable of musical representation, and the only ones likely to endure the tests of time. Rather: we can read the first-century Greek epitaph and not the tenth-century Frankish plainchant because we adopted the musical priorities of the Greeks, and not the Franks. The representation of discrete pitches and rhythms—indeed, of musical parameters at all—was, and remains, a choice, not a necessity. In retrospect it may seem like the obvious choice, but this is because we have been trained to believe that pitch and rhythm are the important musical data: that first and foremost, it is essential to play the "right notes." But, at least in some contexts, musical interest may have nothing to do with the right notes. It may exist beyond the realm of precise measurement, irreducible to a mathematical parameter. It may, indeed, be the negation of measurability and representation: the "liveness" of the improvisor, the rubato of the Romantic pianist, or Baroque ornament. Even if is is measurable or representable, it may lie outside the narrow scope of acoustic data: the physicality of the performer, or the unpredictable properties of acoustic spaces. In short: given the huge variety of what could be musically important, there is nothing obvious about the privilege of pitch and rhythm.

Notation Dates

So how did we get from staffless neumes to the apparent homogeneity and logic of "conventional notation"? Illogically, of course, through the long accumulation and confusion of heterogeneous elements. Let's play the game with notation that we played with Audacity, isolating these elements and identifying their separate origins and histories. Whereas an audio-editing program encapsulates and equalizes a hundred years of music technology, notation collapses a millennium of history onto the flatness of the page. You identify the visual elements, and I'll tell you when they're from:

pitch notation

staff lines

Daseian notation, ca. 800–900 AD

Example of Daseian notation. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daseian_notation)

four-line staff: ca. 1000

- Online example: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LmUWbLNrlrY&feature=related

- Note G clef on second line from the bottom

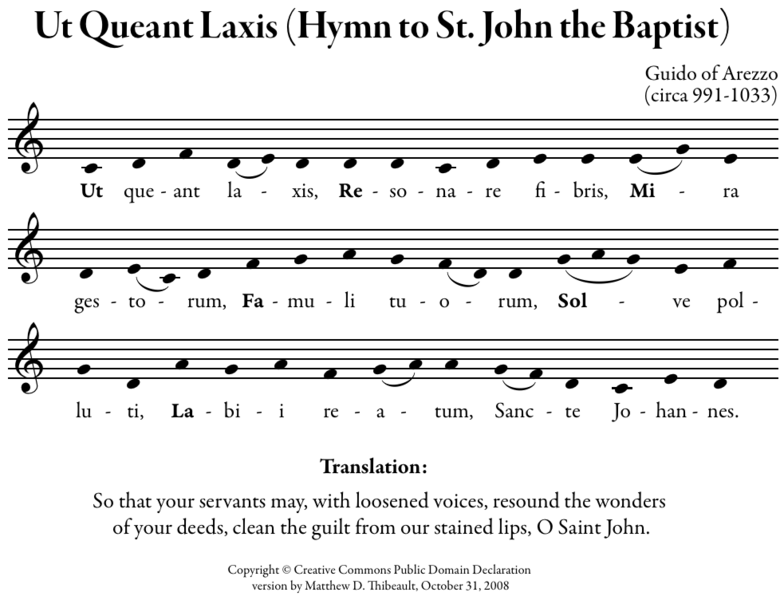

Reproduction of the hymn Ut queant laxis (clef shows where C is; the hymn starts on G below middle C). YouTube performance: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SugtS3tqsoo

The same hymn transcribed in modern notation, and transposed up a perfect fourth.

- Online example: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LmUWbLNrlrY&feature=related

modern five-line staff: ...

clef: ...

key signature

- One-flat signature from earliest staff manuscripts, 11th–12th c.

- "association of a signature with a definite key is a late 18th-century development" (Grove Music Online, "Key Signature")

rhythmic notation

stems indicating duration: Ars Nova, early 1320's

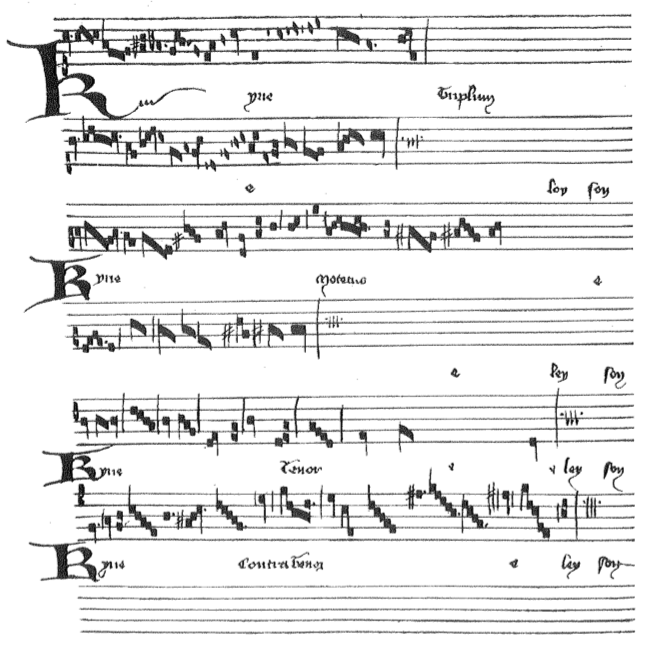

Machaut mass manuscript, 14th c. (I think)

- Ensemble Organum recording: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Y1O-BcZQwY

- Tenores di Bitti: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EsS9xYFKy6c&feature=related

- Corsican folk music: XCD 11930

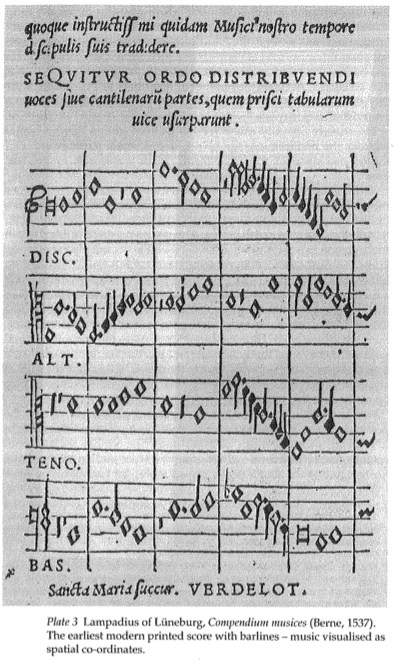

barlines: earliest printed barlines from 1537

Compendium musices, Berne, 1537. (from Daniel Chua, Absolute Music and the Construction of Meaning, 56)

easily recognizable, independent note shapes: 16th c.

time signatures: not standardized until the 19th c.

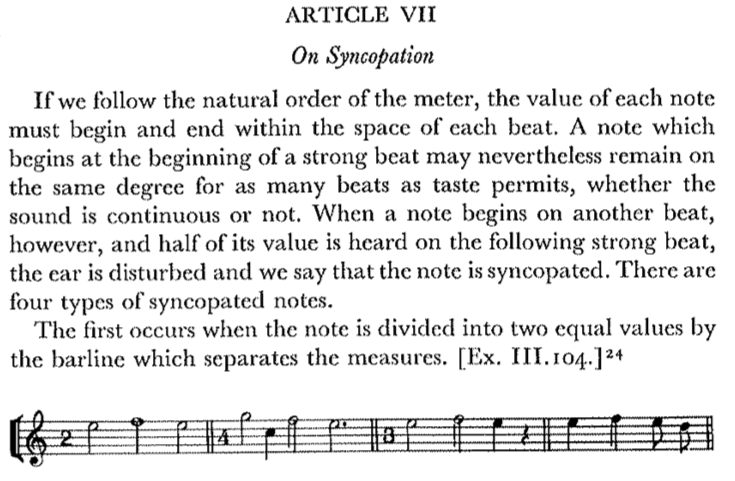

Nonstandard time signature and weird syncopations in Rameau's Treatise on Harmony (Book 3 Article VII, 314)

We will leave some of these innovations and transformations to more diligent historians. For example, unless you object, we will set aside the fascinating history of clefs. Today, we will simply mention in passing the two notational transformations that projected the staffless neumes onto a grid of pitches and rhythms:

- the invention of the staff in the 9th century, which enabled the representation of discrete pitches and polyphony;

- the invention of modal rhythm in the 12th century, which enabled the representation of rhythmic proportions.