Introduction to Jacques Rancière

Contents

Rancière and Kittler

So far in this course, we have relied on Friedrich Kittler's "Gramophone" to guide us through the history of sound technology. In part, we've tried to integrate our material into Kittler's theoretical framework.

This means interpreting sound media as notation systems. Following Kittler, we distinguish between symbolic notation—such as conventional staff notation, chord symbols, and physical instructions—and notation of what Kittler calls "the real"—in other words, acoustic notation, of which the gramophone's inscription of sound waves is the model. For Kittler, the distinction between the two is fundamental, and it's worth repeating.

Symbolic Notation

To produce symbolic music notation, you must borrow or invent arbitrary signs to represent the meaningful structures of the composition. For example, you may use familiar staff notation to represent pitch and harmonic structures, or novel physical notation to represent actions and positions; in either case, you have used symbols to designate meaningful musical structures. What is meaningless you simply do not write down. Symbolic music notation systems interpret the problem of musical reproduction as the problem of musical literacy.

Acoustic Recordings

To produce acoustic notation, you do not produce a sign-system representing music; instead, you produce a recording of sounds. Acoustic notation replaces literacy with the physics of sound; waveforms and frequency graphs circumvent the problem of reading. Sound recording devices such the phonautograph, gramophone, or tape recorder inscribes the physical fact of musical sound, rather than an interpretation of musical meaning. Such devices do not care whether the sounds they record are meaningful or meaningless, as long as they are audible. Recordings allow us to work with sonic data as such, and frees us from the burdens of interpreting musical signs. This is no doubt a relief; it's easier to listen to a Mahler symphony or Stockhausen's "Studie II" than to read their scores. But this liberation comes at a steep price. First, recordings erase any musical information that isn't sonic, such as the visual impression of musicians or their physical gestures. We've discussed some music for which visual and physical data are as important, perhaps even more important, than the sound itself. Furthermore, acoustic notation's indifference to sonic meaning cuts both ways: the power to record meaningless sound along with the meaningful is simultaneously its impotence to provide a framework for musical interpretation. [1]

| [1] | As a side note, this is why we've asked you to produce both scores and recordings for your compositions. |

Thanks to Kittler, we have a vocabulary to discuss these competing notation systems. But Kittler gives us more: following "Gramophone," we also have a methodology that interprets the historical transformations of media technology as fundamental to human perception, creation, and thought. Media technologies are, for Kittler, the basic, self-evident facts of existence: "Media," Kittler writes, "determine our situation." [2]. More specifically, media determine music: its production, its reception, and its philosophy. The precedence of media with respect to music is clear throughout Kittler's work, and although "Gramophone" is full of examples, I'd like to share one from an article called "Opera in the Light of Technology." Kittler reminds the reader that before the invention of gas and electric lighting, the length of an opera was constrained by the time it took for a candle to burn out:

On the baroque stage all performances had to adhere in verse and music to an invisible limit, now thoroughly forgotten: the essence and existence of art were determined simply by the finite burning time of the candles that illuminated both stage and auditorium." [3]

Perhaps this is an extreme case of technological determinism, but it makes the point.

| [2] | Gramophone Film Typewriter, "Preface," xxxix. |

| [3] | Languages of Visuality, "Opera in the Light of Technology," 73. |

The primacy of the sensible: Rancière

While borrowing liberally from Kittler's history of sound technology, however, we have tried to make a point that is at odds with his critical project. Whereas Kittler argues that media determine our situation, we contend that composers have agency over their creative decisions. In particular, they may choose to interrupt the smooth flow of available technologies by deliberately mishandling familiar musical media, transforming unlikely objects into musical material, and generally working around conventional media techniques. Hence our emphasis on musical sabotage, hardware hacking, and composition with strange data flows. These are all activities meant to demonstrate that musical thought and practice are more fundamental than media—that, contrary to Kittler, art reconfigures media, or at least can reconfigure media.

We chose the short article by Jacques Rancière, "Metamorphosis of the Muses," to give critical weight to this argument. Rancière and Kittler have much in common. The philosopher and historian Michel Foucault looms over both of their work.

- Foucault on Bachelard: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=am6TghIrYEc

Their histories, like Foucault's, are histories of rupture and conflict rather than of smooth transitions. In their hands, history becomes a tool of surprise and alienation, a tool they wield to problematize the dominant thought of the present by presenting historical alternatives to it. Beyond their methodological debt to Foucault, Rancière and Kittler are both interested in the alliances of philosophy, art, and technology, and to a degree they even study the same historical periods: namely ancient Greece, nineteenth-century Germany, and twentieth- and twenty-first century Europe.

But here their similarities end. Rancière, like us, flips Kittler's argument on its head, reversing its cause and effect. What is at stake, he argues, is not how the new media produce a new artistic thought and practice, but—vice versa—how a new artistic thought and practice make the new media valid artistic tools. For Rancière "the technological revolution comes after the aesthetic revolution" [4]. Speaking of photography, Rancière writes:

In order for the mechanical arts to be able to confer visibility on the masses. . . .they first need to be recognized as arts. That is to say that they first need to be put into practice and recognized as something other than techniques of reproduction or transmission. [5]

What makes the camera available as an artistic device, and not simply, say, a scientific instrument, or a tool for documentation? What makes its photos of everyday objects art, and not simply data? What philosophical and perceptual framework makes it possible to consider everyday objects as art objects? We can ask similar questions about sound technology. Certainly, the gramophone could record noises that were impossible to capture with traditional notation. But how could people think these noises were musical, if they didn't come from conventional musical instruments? Turning to "Metamorphosis of the Muses", we'll try to understand Rancière's answer.

| [4] | The Politics of Aesthetics, "Mechanical Arts and the Promotion of the Anonymous", 32 |

| [5] | The Politics of Aesthetics, "Mechanical Arts and the Promotion of the Anonymous", 33 |

The contradictions of art

Metamorphosis of the Muses opens with the description of a sound-art installation. Rancière acknowledges the technological dimension of the installation, its "loudspeakers and screens" (17), but he is not interested in going into the history of this equipment; he is not interested in portraying this installation as the mere result of available technology, as Kittler might argue. Rancière is interested, rather, in the way these sound-art installations double as philosophical statements about themselves. The subject of this art, in other words, is the story of art itself: about artistic material and the conditions necessary to produce it. Rancière identifies "two great metaphors of aesthetic ultima ratio"—in other words, the two main themes of the story of this art. On one hand, a cloud of light and sound, which "engenders all form and all melody within its eternal desirelessness"; on the other, the "sovereign artistic will" of the artist, which "grabs hold of all matter, form, or technique," making art out of whatever it can find.

These metaphors, taken together, are the principle of sound-art. As Rancière notes, it is a contradictory correspondence, and it is worth taking a moment to understand why. The cloud of light and sound reveals that matter itself is immanently artistic, as the expression of a desireless, passive spirit. But art is at the same time the product of active artists, who shape and transform whatever material comes into their hands. Art is this relation of passive, spiritualized matter—any matter—to an active artistic will. But here lies the contradiction. Despite their correspondence, the active will and passive matter are radically independent from each other. The will of the artist, while it may sculpt and shape material, has no effect on its artistic potential. All matter is inherently artistic, so the artist's work is superfluous; and yet, for art to mean anything at all—that is, for art to distinguish itself from matter—it much bear the mark of the artist's labor. The artist's labor is therefore both essential and irrelevant to the production of art. The contradiction, however, runs even deeper than that. If all material is available to art, then any willful manipulation of it—not just the artist's—is valid as as artistic technique. Artistic labor becomes indistinguishable from labor in general, and artists become indistinguishable from non-artists. This means also that the perception of an object as an art object has nothing to do with the intensions of its producer. From this perspective art is art on the condition that it is radically indistinct from non-art.

This logic may strike you as circuitous and infuriating. To apply it to a concrete example let's return to the problem that came up on Tuesday, as to whether the carpet is or is not a piece of sound-art. Rancière's answer would be—both: it is, and it is not. It is for the simple reason that it is matter bearing the mark of labor; whether that labor was intended to shape the carpet as an art-object is irrelevant. We can perceive the carpet as sound-art, and that is enough to make it sound-art. But we can only perceive the carpet as sound-art on the condition that we can also perceive it as not sound-art: and clearly, it is also just a carpet.

It is easy to say that all material is available for art, without thinking this idea through to its logical (or illogical) conclusions. Indeed, the conclusions are uncomfortable for those of us who identify as artists, and who would still like to believe that, while all material is artistically equal, some material—our material—may be more equal than others. Most of us would like to believe that the "anything goes" philosophy simply gives us greater flexibility in our choice of instruments, media, and techniques. Rancière's article demonstrates that we get a good deal more than we bargained for: "anything goes" means, fundamentally, the radical indeterminacy of art and non-art. Rancière does not try to resolve this contradiction; indeed, he believes this would be a futile effort, as the last sentence of the article makes clear:

The politics of art which redistributes the forms and time, the images and the signs of common experience will always remain ultimately undecidable. (29)

Nor will he blame the problem on the developments or confusions of technology. He believes that although multimedia technology may give artistic indeterminacy its clearest formulation, it is not responsible for our way of understanding art. The problem, he argues, is philosophical and perceptual before it is technological.

Regimes of art

Rather than outlining a history of music technology, then, Rancière directs his efforts towards answering a different question: was art always indistinct from non-art, as it is for us? What other ways are there to understand art, and "audio-spatial" art in particular? Rancière gives us a brief history of artistic philosophies to help us contextualize the contradiction of an art that's indistinguishable from its opposite. Even before discussing Rancière's account of this history, it's worth noting a conflict in our own manner of thinking about art that should be self-evident: even today, not everyone subscribes to the "anything goes" philosophy of art. Most people believe that paintings, poems, and songs are types of art, and that a carpet is not art. These people are not only the curmudgeonly reactionaries who rage against Rauchenberg's "White Paintings", Cage's 4'33", and Times Square sound installations, but also those who believe that a music conservatory should teach students how to play the piano rather than how to install a carpet. They are those who would argue for any distinction at all between artists and non-artists, or musicians and non-musicians. As Rancière reminds us, just because we actively shape sounds doesn't mean that we are producing anything inherently more musical than a refrigerator or traffic noise. If we identify as musicians, we still subscribe to a notion that designates at least some proper materials for music-making. Clearly there is a tension in our world between at least two ways of thinking about art: first, as arts, each with their own recognizable media and techniques that distinguish them from each other and other forms of production; second, as art ("art in the singular", Rancière would say), which is indistinguishable from non-art.

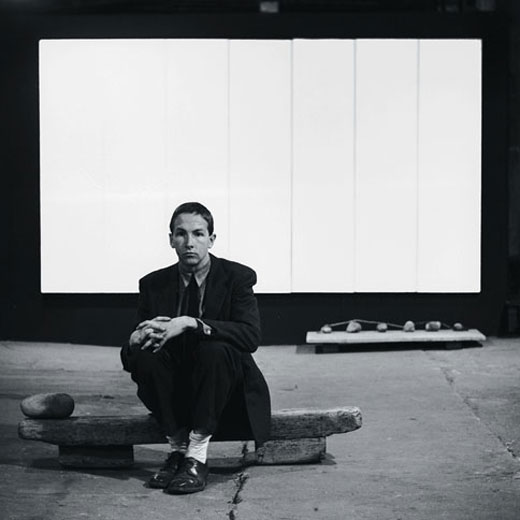

Robert Rauschenberg sits in front of his "White Paintings" [6]

| [6] | http://www.emvergeoning.com/?p=1095 |

In addition to these two opinions of art, we may add the idea that art should be useful above all else. Music, some believe, should help the listener complete a task; it should sync the mind with the body. Music may help the listener relax by soothing his mind with harmonies; alternatively, its rhythms may prepare him for activity, whether a work-out on the elliptical or a military march.

Of course, we may sometimes exercise to pop music, sometimes enjoy sound installations that are indistinguishable from traffic noise, and sometimes practice the piano; nothing forces us to stick to one philosophy of music or the other. Yet it is possible to distinguish each philosophy from the others, and to trace its origins, and this is precisely what Rancière sets out to do.

Regimes of Art

Ethical order

"Let us begin at the beginning" (AaiD 28)

Rancière starts with the philosophy of usefulness, which he calls the ethical regime of art. This is the earliest philosophy of art and music, which makes it a good starting point; Rancière attributes to Plato, but in fact it dates back even earlier, to the mythical pre-Socratic philosopher Pythagoras. This philosophy emphasizes "the mathematical and ethical essence of music", and "the submission of the multiple to the law of unity" (20). In this model, music is suppose to binds citizens to their virtue. The Pythagorean cult embodies this order in its purest, most extreme form:

[T]he whole Pythagoric school produced by certain appropriate songs, what they called exartysis or adaptation, synarmoge or elegance of manners, and epaphe or contact, usefully conducting the dispositions of the soul to passions contrary to those which it before possessed. For when they went to bed they purified the reasoning power from the pertubations and noises to which it had been exposed during the day, by certain odes and peculiar songs, and by this means procured for themselves tranquil sleep, and few and good dreams. But when they rose from bed, they again liberated themselves from the torpor and heaviness of sleep, by songs of another kind. Sometimes, also, by musical sounds alone, unaccompanied with words, they healed the passions of the soul and certain diseases, enchanting, as they say, in reality. After this manner, therefore, Pythagoras through music produced the most benficial correction of human manners and lives. (Taylor's Life of Pythagoras, 61)

Representative order

The representative order has its origins in Aristotle's Poetics, in which the Greek philosopher outlines a hierarchy of the arts based on the tragic poem. On one hand, Aristotle liberates music from Platonic usefulness by granting it its own mimetic role: music need not educate, but may instead tell stories and imitate passions. On the other hand, Aristotle does not allow music to serve as its own model; rather, it must imitate speech. In the history of European music, this Aristotelian model culminates in Baroque musical thought, as is clear from this excerpt from the eighteenth-century philosophe Diderot:

What's the musician's model or the model of a melody? It's declamation, if the model is alive and thinking; it's noise, if the model is inanimate. You must think of declamation as a line, and the melody as another line which winds along the first. The more this declamation, the basis of the melody, is strong and true, the more the melody which matches it will intersect it in a greater number of points. And the truer the melody, the more beautiful it will be. (Diderot, Rameau's Nephew)

Aesthetic order

Finally, there is the aesthetic order, the order that breaks the bond linking thought and labor, frees art from the responsibility of imitating speech, and renders the difference between art and non-art indistinct. Whereas most philosophers interpret these developments as twentieth-century phenomena, Rancière dates them to Romantic philosophy and literature in the late 1700's and early 1800's. This is clear from the from Rancière's example of Glänzenden Geisterscheinung. The German writer Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder, describing his experience of guitar music, is struck by the correspondence between "the technical device and the song of inner life" (Rancière, Aesthetics and its Discontents, 7), between conscious effort and unconscious effect:

But, from what sort of magic potion does the aroma of this brilliant apparition rise up? – I look, – and find nothing but a wretched web of numerical proportions, represented concretely on perforated wood, on constructions of gut string and brass wire. – This is almost more wondrous, and I should like to believe that the invisible harp of God sounds along with our notes and contributes the heavenly power to the human web of digits. (Ibid., footnote)

Conclusion

The tension between Rancière's aesthetic and poetic regimes of art (or music) is evident in this interview with John Cage:

On one hand, there is the music that "speaks" through musical conventions: the music that expresses "feelings" and "ideas of relationships"; the symphonies and sonatas of Mozart and Beethoven. This is the music of the representative order. On the other there is music that is no different from non-music: the noise of traffic and laughter, music which means nothing beyond the facts of production and listening. This is the music of the aesthetic order. Cage prefers the traffic to Mozart. But to believe truly that any sound is available for music is to hear both engines and sonatas from the same perspective: as the indifferent noise of labor radically divorced the worker's intent, whether that worker is an auto mechanic or a composer.

This document was generated on 2011-12-20 at 14:07.