Analog Synthesizers

Contents

Introduction

From the phonograph to the gramophone (with a brief detour to the phonautograph) to the tape recorder to the analog synthesizer: this is the historical, technological, and musical path we have traced so far. The analog synthesizer marks the point, for me, at which the history of technological sound media becomes autobiographical (and a bit sentimental). To be honest, I have never wound up a phonograph, inscribed vibrations on a sooty glass plate, or even spliced audio tape, but I have spent many hours exploring the wonders and frustrations of sound circuitry. I spent perhaps too much of my undergraduate music education learning to play the analog synthesizers in Harvard University's Electronic Music Studio. It was there that, as a classical pianist with conservative training, I overcame my fear of electrocution and first experienced the pleasures of sounds that escaped, in Kittler's terms, "the bottleneck of the signifier." [1] For the first time in my musical life, I felt free to produce music on instruments that defied traditional notation. I was seduced by the dream of synthetic sound—the dream of designing sound patterns from electrical signals themselves; a dream of lines and curves, pure musical shapes and patterns. Now that you have built an (admittedly crude) oscillator, I hope you can understand this seduction, even if you can't relate to it directly.

| [1] | GFT 4. |

The Prehistory of Analog Synthesis: Sound-Writing

Kittler reminds us that artists, writers, and filmmakers (and engineers, of course) dreamt this dream before composers like Stockhausen and Oliveros turned it into their own reality:

Moholy-Nagy already suggested in 1923 turning "the gramophone from an instrument of reproduction into a productive one, generating acoustic phenomena without any previous acoustic existence by scratiching the necessary marks onto the record." An obvious analogy to Rilke's suggestion of eliciting sounds from the skull that were not the result of a prior graphic transformation. [2]

| [2] | GFT 46. |

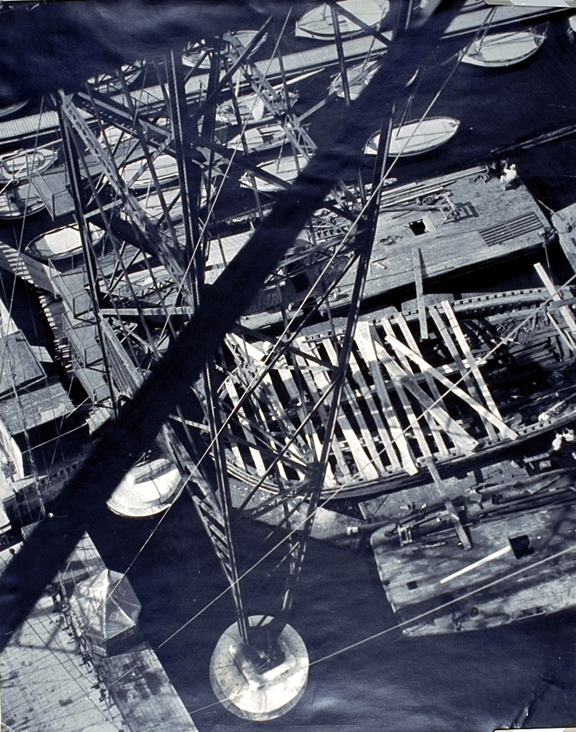

László Moholy-Nagy's Vom Funkturm (From the Radio Tower), 1929. [3]

Moholy-Nagy's poster for the Bauhaus Exhibition in 1923. [4]

Moholy-Nagy was a photographer, painter, filmmaker, and media experimentalist who taught at the Bauhaus. His suggestion, and Rilke's, illustrate the increasing confusion between musical sound and data flows in general: "Any graphisms—including those, not coincidentally, dominating Mondrian's paintings—result in a sound." [5]

| [3] | http://www.shafe.co.uk/art/L%C3%A1szl%C3%B3_Moholy-Nagy_-_Funkturm_(radio_tower)_Berlin-_1926.asp |

| [4] | http://grafikplastik.blogspot.com/2009/11/mastering-my-roots.html |

| [5] | GFT 46. |

Before the oscillations of sound-circuits, there were the etchings of sound-animators. Rudolf Pfenniger, Oskar Fischinger, and, more recently, Norman McLaren drew directly onto the optical soundtracks of film to produce the synthetic square, triangle, and sine waves that later formed the basis of the analog synthesist's sound-palette. [Norman McLaren Synchromy clip: square waves] [6]

| [6] | "Tones from out of Nowhere" is an excellent article on this topic. |

Analog Synthesis in the 1950s and 1960s

NWDR

The dream survived World War II and entranced the engineer-composers of the Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk (NWDR), or Northwest German Broadcasting—among them, the young Karlheinz Stockhausen. In Stockhausen's pre-sixties work, the dream becomes a full-blown, megalomanical obsession with sound-sculpting on the atomic scale and the rigorous control of sonic parameters. This was in line with the German studio's aesthetic, and it must have struck the French musique concrète practitioners as, frankly, fascist. (Aside: were they right? Consider far-right and far-left historical precedents: futurism on one side, the Bauhaus on the other.) A Dutch composer working at the NWDR notes:

You could say that in the '50s, you had two types of Cold War. One between the Soviet Union and the United States and one between the Cologne studio and the French studio. They disgusted each other. The aesthetic starting points of Schaeffer were completely different from Eimert's [the Cologne studio director's] views. [7]

| [7] | Konrad Boehmer, quoted in Electronic and Experimental Music, 56 |

Oliveros

How did the dream of synthetic sound-writing and the tools of analog synthesis then spread from the uptight NWDR and Karlheinz Stockhausen to the free-wheeling San Francisco Tape Music Center and Pauline Oliveros? This may seem like a stretch, but a couple facts shorten the (aesthetic) distance considerably (though I can't account for the technological distance):

- Several composers in the San Francisco scene (La Monte Young in 1959 [8], Morton Subotnick in ??) attended the Darmstadt summer courses, which were a point of intersection between the American experimental aesthetic and the European avant-garde aesthetic. (Ironically, Darmstadt was also where Americans could learn about what was happening elsewhere in America; e.g. it's where La Monte Young met David Tudor [9])

- While Stockhausen never became less of a megalomaniac, he did loosen up in the sixties. Compare his instruction piece "Connection," from Aus den Sieben Tagen in 1968, to Olivero's "Native" from Sonic Meditations, 1974:

Stockhausen's "Connection."

Olivero's "Native."

| [8] | The San Francisco Tape Music Center 99. |

| [9] | Ibid. |

Commercialization

Then the dream of synthetic sound-writing became a profitable reality. As with the other sound technologies we have seen, what began as scattered, irregular instruments for sound research and musical experiment became normalized and mass-produced as money-making machines. Bob Moog's keyboard interfaces were the technological innovation—or retrogression, depending on your point of view— that made the analog synth commercially viable.

A peak into Giorgio Moroder's studio in the late 70's shows the commercial state of the art: not exactly hippies working with what they had in a rented Haight-Ashbury apartment, but a music studio to make even NASA jealous:

Death and Rebirth

By the late seventies, digital music technologies began to supplement analog ones, as you can see in Giorgio Moroder's promo. By the mid-eighties, digital keyboards like the Yamaha DX-7 were ubiquitous, and had largely supplanted their analog predessors. The glory days of analog synthesis had passed. But if you've learned one thing from this class, it's that music technologies die only to be reborn. The electronic studio managers of the Columbia Music Center (CMC), Harvard University Electronic Studio for Electroacoustic Composition, and a few other institutions had the foresight not to discard their older analog synthesizers simply because newer digital technologies became available. As Lachenmann teaches us, music technologies become interesting precisely when they become outdated and overburdened with history. A novel sound technology has no historical dimension to exploit, but with an antequated technology, the production of new sounds may also produce a radical alternative to a familiar history. To end this lecture, I'd like to play a bit of a track by the duo "ExclusiveOr", which is my friends Jeff and Sam:

Jeff Snyder (left) and Sam Pluta, twenty-first-century CMC electronic music geeks posing as 1950's electronic music geeks. Serge and Buchla synthesizers in the background.

As with Lachenmann's piano, this is music that redefines the possibilities of past instruments. In the words of the serious German man who is himself deaf to the history of electronics:

Every noise is as intensive and new as the context you stimulate for it. To liberate it, for a moment at least, from the historic implications loaded into it—this is the real challenge. It is about breaking the old context, by whatever means, to break the sounds, looking into their anatomy. Doing that is an incredible experience. [10]

| [10] | "Interview with Helmut Lachenmann—Toronto, 2003", 10 |

This document was generated on 2011-12-20 at 14:07.